"My son is addicted to video games!" That's a statement I hear frequently, whether the son is a small child, or a young adult. I hear this less often for girls. Although there are a lot of girls heavily involved in games, more often I hear about girls with heavy use of texting and social media. But, for males, so often the gaming, whether on a console or through the internet, can take up as much time as the parents allow. Officially, there is no such thing as video game addiction, at least in the US. China does call it an addiction, and there are treatment programs there and elsewhere. Currently, the DSM-5™lists Internet Gaming Disorder as a condition for further study. It's unfortunate they chose to call it that, because the technology will surely outpace the research, and the behavior around compulsive game play could be the same even if the Internet is not the vehicle of connection. The text in the DSM does allow for the idea of non-Internet computerized games, but it seems like this is going to be very confusing. (Is this a DSM theme, reminiscent of the confusion surrounding non-hyperactive Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder?) The APA, the organization that compiles the DSM and looks at the research, has set up some proposed criteria. As always with disorders, there must be impairment or distress. Then we can look at the issues: preoccupation, withdrawal, tolerance, unsuccessful attempts to cut back, loss of interest in other things. It's looking a lot like what they've written for chemical dependence or gambling addiction, which were the models for this section after all. In the detailed text, the DSM refers to individuals neglecting other activities, missing sleep and food, playing at least 30 hours a week, and becoming angry or agitated if they can't play. All these official details are fine, but for most parents who are worried, the issue of video game addiction comes down to common sense rather than research consensus. Is your child missing out on social, physical, and professional or educational activities because of game time? Is your child using gaming to manage emotions like anxiety, loneliness or boredom? Does your attempt to manage the time result in meltdowns? Is your child developing the important skills of learning to tolerate boredom or complete a task that doesn't reward with exploding rockets and buzzers? Stay tuned for my next post, where I discuss video game addiction specifically for individuals with special needs. photo credit: <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/30806435@N04/4298824267">Playing DS</a> via <a href="http://photopin.com">photopin</a> <a href="https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/">(license)</a> Now that school is getting out for the summer, your family’s schedule may be a lot more relaxed. If your child has special needs, such as an Autism Spectrum Disorder, Asperger’s disorder, ADHD or ADD, organizational and executive functioning issues, or problems with social skills, the school year may have been extremely high stress. It’s great to be able to enjoy this more unstructured time, spend more time together as a family and take it easy. Without the pressures of school and homework, now is also the perfect time to help your child improve social skills for the upcoming school year.

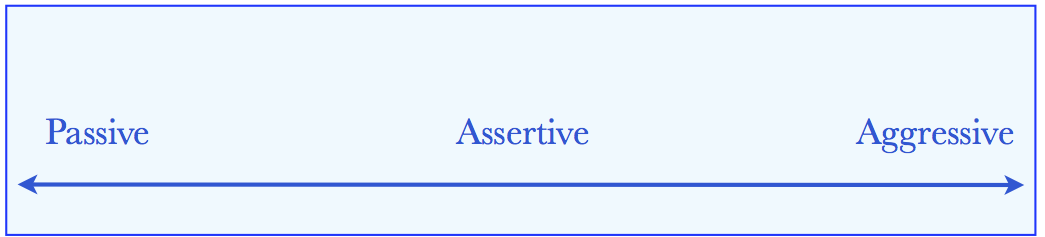

If your child has been struggling with friendships, the summer months can be a great time for unstructured playdates. Many outdoor activities, such as playing in the pool, riding bikes, playing with water balloons or kickballs, are less organized and subtle than more conversational, indoor games. These can be a great opportunity for your child to interact with peers and have fun too. If your child struggles with basic athletic skills, such as swimming, bike riding, running or kicking, or even climbing on the monkey bars, the summer can be a time to work as a family to improve these abilities. Some kids really dislike sports, and have no interest in doing these types of activities, but school playgrounds do revolve around games. If your child can manage to participate, a new social avenue is opened. Kids who aren’t skilled at sports often don’t join in, and then their skills get even further behind. Playing as a family can remove the pressure that your child experiences in peer play. For kids who have spent the school year struggling with organization, the summer is the chance to catch up and get ready for next September. Work together to remove all of last year’s papers and books. Clear the desk and drawers so you have room to work in a more organized setting next year. This may seem far removed from social skills, but remember that the faster and more efficiently your child can finish homework, the more time there is left for other activities. Be sure to keep all these activities light and fun. Kids with special needs have worked hard all year, and so have their parents. You all deserve some time to enjoy each other. Image attribution: by Jairo [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons I frequently work with clients, both kids and adults, on the theme of passive, assertive and aggressive.This is an easy way to calibrate behavior in tricky situations, and a good way to interpret the behavior of others. My desktop dictionary defines passive as “accepting or allowing what happens or what others do, without active response or resistance.” Assertive is “having or showing a confident and forceful personality,” and aggressive is “ready or likely to attack or confront.” I like to think of these three words as defining a continuum, with the passive end considering only the needs and desires of others, and the aggressive end as defending one’s own rights solely, at the expense of others. Assertive fits neatly in the middle, standing up for oneself while still considering others.

In most situations, it pays to lean in the direction of assertive behavior. Speak up for yourself, ask for what you want, object to the things you don’t want. In an earlier post, I talked about a practical and simple technique for dealing with anxiety. In this post I'd like to expand on some of those ideas.

For many individuals on the autism spectrum, anxiety is a constant presence. I find it can be very helpful to view these worries in a more mathematical way. Although many people on the spectrum are very good at math, there's a common belief that math and emotions are two different things. As both an engineer and a therapist, I like to explore the intersection of math and emotion. You don't need to have an advanced understanding of probability theory to use this technique. Simply think about the general odds that something you worried about will actually happen. Usually, worries are quite specific, and are based on the idea that many specific events will have to occur. To think about probability, it's a simple matter to consider how likely each event is. You don't need a great deal of accuracy, but I find it's helpful to have a number, like 1 in 100, rather than a word such as "unlikely" or "rarely". Here's an example. Suppose you're worried about a traffic accident making you late to the airport, so that you miss a flight. If this is a valid worry, then it makes sense to take steps to leave earlier. But, so often, the actual worry is unlikely to happen. That's when looking at probability makes sense. How often is there an accident that causes a delay on the roads? Once per day? How likely is it that the delay will be when you're actually on the road? Once per 2 months? How likely is it that the delay will be more than a few minutes? Although I travel busy Bay Area highways, it's rare that the accidents cause delays of more than a few minutes. Maybe the chances are 1 day in 365 that the delay will be so long I would miss the flight. Does that warrent a great deal of worry? If your worries continue, it can be helpful to do the following tedious yet enlightening exercise. Make a rough estimate of the actual odds of your worry. Create a jar or bowl filled with white pieces of paper, representing everything working out OK, and just enough dark pieces of paper to represent your worry. The chances of one in 1000 could be represented by one piece of blue paper in a sea of 999 pieces of white paper. Although it takes a bit of time, it's not that difficult to cut many scraps of paper by stacking sheets. It's also helpful to see just how long it takes to cut 999 pieces of paper as compared to the one piece of blue paper. I find that the actual exercise of pulling papers from the jar repeatedly helps to illustrate in an experiential way exactly how unlikely many worries are. Then you get to take the same steps I suggested in the earlier post. Manage the emotion of anxiety, and take the practical steps to deal with the issues as well. Does it really matter how you come across at work if you get your job done? So many of my clients tell me that it doesn't. True, you're hired because of your abilities, often a technical skill or a specific knowledge. But once you get the job, it's no longer just about that skill or knowledge. Now, you're part of a team, assigned to all sorts of projects that may have nothing to do with your expertise.

You may be the world's leading expert on a specific user interface, or an aligner, or 17th century Norwegian artists, but once you get the job, you'll be put on the party planning committee, or the diverse hiring practices task force, or the workplace safety team. All those extras have nothing to do with your expertise, everything to do with your job success (and job security!) and they all require social skills and a good work attitude. Just like Seth Godin says, "Your smile didn't matter....No Longer." So many individuals with Asperger’s and autism get caught up in worries, repetitive thoughts, ruminations. Often, worry is the number one difficulty that individuals on the autistic spectrum have to deal with. We all face failure, rejection, unpleasant situations and uncomfortable emotions. But the difference in how well you manage is about how well you can let go and move past those difficulties.

Worry is about the past, looking at all the things that have gone wrong for you. And, worry is about the future, recreating all those negative situations and imagining them into the your future. That’s why present based programs, things like Eckhart Tolle’s the Power of Now, or Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction can be so effective: they help you move out of the past, out of the future, and focus on the now. Even a simple step like pausing for a breath or two can reset your anxiety level, move you out of thinking about the past or imagining the future, and take you right into the present moment. “It’s not you, it’s me.” A cliched breakup line? Yes, it is. A true statement? Yes, again.

So often, when I’m talking to people, they’re stressed about someone else’s reaction to something that happened. They told a story, and the listener wasn’t paying attention. They tried to invite someone for lunch and the invitation wasn’t accepted. Or, a close friend has drifted away, for no clear reason. Then they start analyzing, worrying, ruminating. “What did I do wrong?” “Why does this always happen?” What should I do differently next time?” For individuals with any degree of anxiety about social interactions, these “rejections” can feel so devastating, so personal. Of course it’s important to examine the situation, see if you did play some role in things not working out too well. But then, it’s okay to let it go and stop dwelling on it. We all lead busy lives, with so many obligations, pulled in so many different directions. Most of the time, you didn’t do anything wrong. You colleague really does have something else to do at lunchtime. Or, your story was fine, the listener was just caught up in remembering an important obligation. Often, the true social damage happens after this minor disconnect. An insecure individual can read too much into it, start over-thinking, get too worried, pull back too much, turn a little issue into a big pattern of social issues. On the other hand, socially confident people assume the best, about their ability to be a good friend, and their interactions with others. If a friend says he’s busy, they assume he is, and issue the invitation again. If an invitation is rejected, they try again. After all, chances are, it’s about them, not you. Managing emotions is a challenge for many individuals, young or old, whether neurotypical or somewhere on the autism spectrum. Everyone’s struggles are a bit different, with some people veering toward worry and anxiety, others tending to sadness or depression and still others prone to anger. A great deal of my work as a therapist is in helping people manage their troubling emotions, whatever emotions they happen to be.

When working with emotions, it’s helpful to pay attention to the feelings of the body, the actual somatic sensations. Many individuals are more comfortable staying in their heads, intellectualizing and reasoning, rather than physically feeling. If you’re intellectual, pride yourself on your academic achievements or thinking strengths, this could apply to you. If you struggle with overwhelming sensory issues, or physical activities like athletics, then it’s not surprising if you also avoid the more bodily experiences of emotions. The best way to manage feelings is to actually feel them. Try it now. Stop talking, stop doing anything, try to quiet that conversation in your head. Take a breath, and feel what’s going on in your body. There are several opinions about teaching children with special needs to use scripted social skills. For kids who struggle with reading and sending social messages, such as those with Asperger’s Disorder, Autistic Spectrum Disorders including Nonverbal Learning Disorder (NLD), as well as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADD or ADHD), figuring out subtle messages can be much too challenging. A set of scripted, simple rules and guidelines may be useful in getting a general plan of action. (An example of a scripted response might be, “Say hello when you walk up to one person, but not when you enter the classroom.”) At the same time, trying to memorize and apply dozens of social rules can be overwhelming. It may even backfire because a person attempting to apply specific rules while in the midst of a confusing situation is not going to be able to focus on reading what’s going on. As is usually the case, I think the optimal answer lies somewhere in the middle.

Ideally, parents, teachers and therapists should be helping children figure out how to read social cues and how to naturally respond to them. This may accomplished in a completely organic way, with a parent getting a “hello” back from an engaged baby. In more difficult situations, trained adults can be working deliberately to engage the child and get a natural response. This is similar to techniques that might be used in Dr. Stanley Greenspan’s DIR® and Floortime™ model. Setting up frequent playdates gives the child the opportunity to interact frequently with peers and may be a way to give practice in reading and responding to social cues in a natural and unscripted manner. This can be tricky because kids who are socially skilled are probably not going to adapt their interactions to be less subtle or more engaging in order to interact with a child who is struggling. Too often the socially skilled children will just stop playing with, or worse, start teasing or excluding the less skilled children. Playdates with two or more children who are all struggling socially may be the best choice for allowing friendships to develop and social skills to grow. This situation is not without its challenges. Some degree of adult involvement may be necessary in order to ease the relationship. For example, initiating a playdate may be the most challenging step. Teachers and parents may have to help set up the initial connection. While the children are playing, it may be necessary to have an adult present to help all the children interact smoothly. Because all the children may struggle to both read and send signals, the interactions can be difficult for everyone. When all goes well, the children can develop truly deep and important friendships that move beyond the more formal playdate setting. In addition, the skills are learned in a realistic way, so the problems with generalizing lessons to a different setting don’t occur. When more natural interactions with adults and peers are not effective, then formal, scripted skills may be helpful. I view these scripts and rules as a way to ease into more ordinary, real-life interactions. An example of this might be a teacher prompting a shy child on how to approach a classmate, so they can sit together for lunch. Here, the most productive interactions will occur when the kids are eating and talking together without the teacher, but the more formal rules will help the child get to that point. This example really illustrates the ideal situation. Allow the child to have as many natural and rewarding interactions with others, both children and adults, as possible. Use more formal social skills training to ensure that these natural interactions can take place and that they run smoothly. Take the time to analyze and understand the subtleties, and more important, set up a plan to make the interactions more productive next time. Anger can be a scary emotion, and many people try to suppress it. Kids may think they’re not allowed to get angry, parents may not want their kids to show their anger, and adults may think anger is, somehow, wrong. The reality is that anger is a part of being human. Anger allows us to feel the injustice of situations, it helps us set healthy boundaries, and it can provide the power to make great changes.

Most small children start expressing anger when they don’t get something that they want. That’s still true of older kids and adults, but as children develop, they also will get angry when they perceive a situation as unfair. Our innate sense of justice gets triggered, especially when we’re the ones being mistreated. The goal in anger management is not to get rid of or suppress anger, it’s to allow the emotion in a healthy and even a useful way. I often ask clients, “How are you allowed to express anger?” Frequently, the question is answered with a puzzled silence or, “But, I’m not allowed to get angry.” My suggestion, to everyone trying to manage anger, is to think in advance about what’s allowed. Parents should discuss anger with their kids, during a calm time. What are the family rules about anger? Some families forbid the use of certain words, name-calling, breaking things, throwing things. Other families are more liberal. Whatever your family’s rules, there has to be some allowed form of anger expression. And remember, siblings get mad at each other. That doesn’t mean they hate each other, or that they will not get along in the future. For adults, just acknowledging your own anger may make you feel better. Writing in a journal, or writing (not mailing!) a letter can get the thoughts out of your head. Physical activity, like running or dancing, may help use that energy up. Others feel better if they put their emotions into creative activities. Music can be either expressive or soothing. Focusing on change may make anger easier to manage, whether it’s starting a neighborhood watch, or thinking about what you can control in your marriage. It’s important to pay attention to how the emotion of anger feels, physically in your body. So many people tend to be head oriented, they forget about the body. And, the body is where emotions live. Being more body focused can help you manage your feelings and move on. For more on this topic, be sure to check out my earlier blog posts on anger management. Anger Management and Asperger's, Part I: Understanding Anger and Anger Management and Asperger's, Part II The Feeling of Anger. |

Patricia Robinson MFT

I'm a licensed therapist in Danville, California and a coach for Asperger's and ADHD nationwide. I work with individuals of all ages who have special needs, like Autism Spectrum Disorders, ADD, ADHD, and the family members and partners of special needs individuals. Archives

February 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed